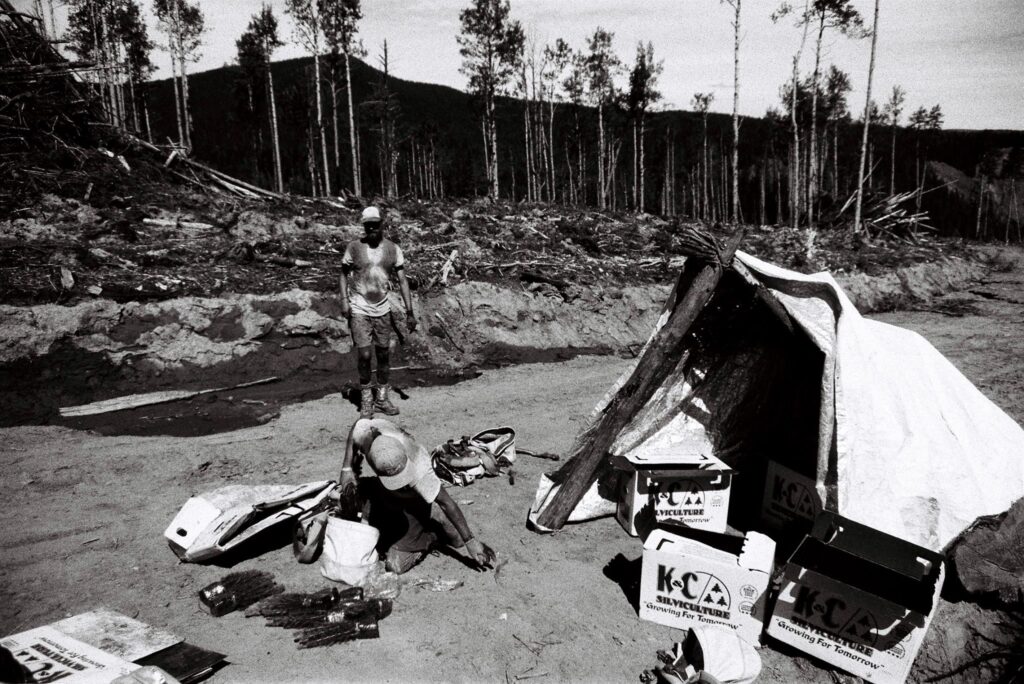

The job attracts a wide range of characters; from hippies looking for a nature-filled adventure, to students desperately trying to pay their debts, to outcasts who started tree planting one day and never found a good reason to stop.

I went tree planting because I wanted to travel across Canada and do something new while making good money. I was 19 and didn’t want to commit to school or a regular day job. Some of my cousins had planted and one of them became a crew boss so I asked him for a job. I had heard several stories about the nature of the work including some that turned out to be tall tales.

My flight arrived in Northern B.C. in early May and I was picked up with another first-year, or rookie, that had sat in front of me on the plane (and who I would end up planting with for years). The timing worked out well because I hadn’t made any proper arrangements and the camp was over two hours from town. We drove there in the typical tree planting vehicle called a crummy which is essentially the body of a bus welded onto a heavy-duty pick-up. The windows often have bars over them giving it a prison bus sort of feel. My camp supervisor referred to them as death machines.

When we pulled in people were drinking around a fire. It was dark and there was snow on the ground where we were supposed to set up our tents. I wasn’t prepared and brought a cheap sleeping bag and no sleeping mat. The first few nights were cold and restless until I was able to buy better gear on our next trip to town. I used my sweater as a pillow and rolled over when I felt my side getting numb from the ground.

I was motivated to be the best rookie and my confidence lasted a few hours into our first day. I quickly and unknowingly incorporated the rookie stare into my repertoire. This consists of looking confusedly at the ground or staring off into the distance after a short while of searching for a good spot to plant a tree. My foreman told me to settle into a boxing stance before bending over instead of my back-bending style. I planted fewer trees than several of the other planters and the whole crew was told to stop halfway through the day and replant our faulty trees. We were making 12 cents per tree and were not paid for replanting.

My cousin/crew boss had five seasons under his belt and instead of planting thousands of trees every day, he now had to babysit a number of clueless first-years. Our crew had about fifteen planters and only two or three were vets. Ideally, there are more vets who can teach the rookies. The company did its best to keep the boy/girl ratio at around 50/50.

At first, many rookies plant under 1000 trees per day but quickly improve. After reaching 1000 the next goal is 1500 and then 2000 and so on. If a planter doesn’t plant enough to earn much money, some companies will top them up to minimum wage. Our company did this for the first 10 days of the season—after that, the difference came out of the foremen’s pocket. At that point, the foreman would decide whether or not it’s worth keeping you on. At 12 cents per tree, the minimum wage was around 1000 trees at that time.

Some planters learn the job and become comfortable with working at an easy pace while still making decent money. Other planters push themselves and compete with one another and some are in it for the money alone. One Quebecois planter told me, “The ground is your bank and the trees are your money!”

If there is no driving access to the block (where the trees are planted) you can take a helicopter. We would usually fly in an A-Star which is a fairly small five-seater that easily floats off the ground. The biggest helicopter we used was called a B205 or something like that. It was a 15-seater and would chug back and forth during takeoff making it much more intense.

On the crummy/helicopter ride home from the block you often feel a sense of accomplishment. Your arms are dark from the sun and dirt and are shiny with sweat. When you arrive at camp there is a meal waiting for you. I was lucky enough to have great cooks every year I planted. The food is served out of a trailer or cook-shack through a cut-out window. The meals are different every night and planters gather around in the mess tent and eat together. When the cooks were wound up they would shoot tequila into our mouths with water guns from the cook-shack window.

My first camp was outside of Smithers B.C. To get there you drive about 40 km North, take a left and drive another 40 kms West and you’ve made it. It was a gravel opening in the middle of the forest. At the West end, there was the mess tent. Beside it was the shower tent with four shower heads separated by tarps with pallets to stand on. On the East side of camp by the entrance was a long line of crummys, box trucks and fuel trucks. Between the trucks and the mess tent there was a fire pit surrounded by miscellaneous chairs and couches and about thirty feet North of the pit there was a sparse forest ending at the road. In the forest, there was a maze of tents, clotheslines, hammocks and other obstacles that you had to memorize if you wanted to safely navigate at night.

On a work day, breakfast is often at 6 am and dinner at 6 pm. Before eating I packed a lunch which usually involved a couple of peanut butter banana wraps, some fruit and some block treats. During the bumpy drive to the block, there is often music playing in the back of the crummy and many planters are sleeping or wrapping duct tape around their fingers for extra protection. When we arrived at the block our foreman would give us a map with our piece of land on it and go over the plan for the day. After that, everyone would part ways to their separate caches (piles of tree boxes).

A planting box usually holds anywhere from 270 to 420 trees and a common bag-up is about 360 trees (roughly 60 lbs). If a planter reaches 2000 trees at 12 cents they make $240, for 3000—$360, 4000—$480 and so on. By the end of the season, the highballers often make $500+ a day (prices vary depending on the difficulty of the land).

We worked three-and-ones (three days on and one off) which is a common tree planting shift. On day three, planters summon what energy they have left and let loose. Some nights evolved into a booze-fuelled dance party in the back of a five-ton, while others became a mushroom-induced night around the campfire.

The morning after a night off, planters linger around the mess tent and those who want to go to town can hop in a crummy. As the last crummy pulls out there’s often one frantic planter on its tail just moments after falling out of their tent and scrambling to collect their dirty laundry.

There were usually three crews in our camp and over the course of the season everyone became pretty close—especially with their own crew. There were a few camp moves during the season and sometimes that meant losing a crew to another camp or gaining some new faces.

Some of the best times came during camp moves. Everyone piles their tents and belongings into the foreman’s box truck and packs up the entire camp. Then we begin the drive to wherever the new camp is (usually far away). There are often a few days off and planters stay in cheap motels along the way. One motel room naturally becomes the centre of the party and has to endure all the sloppy planters.

One of the best things about planting is being in a remote place away from the “real world” and often having no internet or cell reception. Everyone sits around the campfire or mess tent and talks without distraction. If you’re looking for something that can make you good money and toughen you up, go tree planting. You will learn to push yourself harder than ever and meet all kinds of characters in the process.

Always wanted to try it, this post may just be the ticket